Recitation 11

Recitation notes for the week of November 5, 2025.

HW 6, Question 1

Part (a)

A Clarification

Even though it is not required by the problem, we present the algorithm idea, proof idea and proof details.

Algorithm Idea

Our goal is a $O(\log{n})$ divide and conquer algorithm for computing $f_2$, so we should try to construct an algorithm that does divide and conquer with one subproblem, and has a constant amount of queries per problem, since the recurrence relation $T(n) \le T(\frac{n}{2}) + c$, when solved, gives us $O(\log{n})$ queries (see notes in part (b) for why this is the case). Note that this is the case since the algorithm takes a constant amount of time at each recursion instead of linear.

We can achieve this by recursively dividing the input $x_1,\dots,x_n$ into two subsets and querying them both. Remember that each query returns $1$ if any of the queried nodes is $1$, but doesn't tell you how many in the set are $1$. If both sets return $0$, we are done, and $f_2(x_1,\dots,x_n)=0$, because none of the $x_i$'s are $1$. If both sets return $1$, we are done, and $f_2(x_1,\dots,x_n)=1$ because \textit{at least} $2$ nodes are $1$. If only one set returns $1$, there might be two $1$'s in that set, but there might not, so we must dig deeper. We can ``throw out'' the set that returned $0$ and recurse on the set that returned $1$ as our single subproblem.

Algorithm Details

ComputeF2(input,n)

# input = {x1,...,xn}

Divide {1,...,n} into two disjoint subsets of size n//2 and n-n//2 (call then S1 and S2)

if n==1:

return 0

left = input[1..n//2]

right = input[n//2+1 .. n]

Query S1 and S2.

if Query(S1) == 0 and Query(S2) == 0:

return 0

else if Query(S1) == 1 and Query(S2) == 1:

return 1

else if if Query(S1) == 1:

return ComputeF2(left, n//2)

else:

return ComputeF2(right, n-n//2)

Slight deviation from Walkthrough video

Lines 14 and 15 are not present in the algorithm details in the walkthrough video. However, they have the same asymptotic behavior (convincing yourself of this is left as an (ungraded) exercise!)

Proof Idea

We need to show that if at least two nodes in $\lbrace x_1,\dots,x_n \rbrace$ are $1$, that our algorithm returns $1$, and if one or zero nodes are $1$, that our algorithm returns $0$. We can prove this by showing that two cases can't occur: a false positive (we return $1$ when there are only one or zero true nodes, i.e. $=1$) and a false negative (we return $0$ when in fact $\ge 2$ nodes are true). We will consider each case separately with a proof by contradiction.

Proof Details

First, let's consider the false positive case. Assume to the contrary that $< 2$ nodes are true, but our algorithm returns $1$. If zero nodes are true, then no matter how $\lbrace x_1,\dots,x_n \rbrace$ is divided into two subsets, the queries to both will return $0$, so our algorithm will return $0$ (in line 15), a contradiction. If one node is true, then after dividing $\lbrace x_1,\dots,x_n \rbrace$ into two subsets, our true node (call it $x_j$) will be in either $S_1$ or $S_2$. Since $S_1$ and $S_2$ are disjoint, $x_j$ can't be in both $S_1$ and $S_2$, so the condition that both queries return one will never be satisfied. Likewise, the condition that both queries return zero will never be satisfied, since $x_j$ must be in either $S_1$ or $S_2$. So at each iteration, we will always satisfy the condition that only one query returns $1$, until $x_j$ is in a set of size $1$. However, at this point the algorithm will return $0$ (line 7), a contradiction.

Next, let's consider the false negative case. Assume to the contrary that $k \ge 2$ nodes are true, but our algorithm returns $f_2(\lbrace x_1,\dots,x_n \rbrace)=0$. If at least one true node is in $S_1$ and at least one true node in $S_2$, then the algorithm returns $1$ (line 17), a contradiction. However, suppose the true nodes are all in either $S_1$ or $S_2$. Without loss of generality, we'll assume they're all in $S_1$. This is possible for iterations where $\mid S_1 \mid \ge 3$. However, when $S_1 < 3$ and we divide it into two subsets to query, at least $1$ true node must be in each subset, since the maximum subset size is $1$. Therefore, our algorithm will return $1$ (line 17), a contradiction.

The following you should do on your own:

Exercise

Argue that the above algorithm makes $O(\log{n})$ queries.

Part (b)

We recall the problem:

HW 6 Q1(b)

For any $1\le t\le n$, design an algorithm that can decide the function $f_t$ on any input $x_1,\dots,x_n$ (i.e. for any input $x_1,\dots,x_n$ the algorithm correctly outputs $f_2(x_1,\dots,x_n)$) using only $O\left(t\cdot \log\left(\frac{n}{t}\right)\right)$ queries.

It might be useful to bound the number of queries using a recurrence relation, so we will go over some examples of that next.

Recurrence Relations

$T(n) = T(n/2)+O(1)$

We start off with the Binary search algorithm (stated as a divide and conquer algorithm):

Binary Search

// The inputs are in A[0], ..., A[n-1]; v

l = 0

r = n-1

return binary_search(A,l,r,v)

# Recursive definition of Binary Search

def binary_search(A,l,r,v):

if l == r:

return v == A[l] # Return 1 if A[l]=v and 0 otherwise

else:

m = (l-r)/2

if v <= A[m]:

return binary_search(A,l,m,v)

else:

return binary_search(A,m,r,v)

It is easy to check that every line except the recursive calls of binary_search takes $O(1)$ time. So if $T(n)$ is the runtime of binary_search, then it satisfies the following recurrence relation:

Recurrence Relation 1

\[T(n)\le \begin{cases} c & \text{ if } n=1\\ T(n/2)+c & \text{ otherwise }.\end{cases}.\]

Next, we will argue the following

Lemma 1

For recurrence relation 1 above, \[T(n)\le c\cdot (\log_2{n}+1).\]

Proof Idea

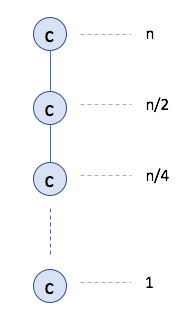

The idea is to unroll the recurrence. Each level has a contribution of $c$:

Since there are at most $\log_2{n}+1$ levels, this implies the claimed bound.

Proof Details

See Page 243 in the textbook.

Exercise 1 (do at home)

Prove the recurrence using the "Guess and verify (by induction)" strategy.

$T(n) = T(n/2) +O(n)$

We now consider the following recurrence relation

Recurrence Relation 2

\[T(n)\le \begin{cases} c & \text{ if } n=1\\ T(n/2)+cn & \text{ otherwise }.\end{cases}.\]

The book on Page 219 solves this recurrence. We do a very quick overview now.

We do the "unroll the recurrence and use the pattern technique." At an arbitrary level $j$, there is one instance, of size $\frac{n}{2^j}$ and contributes $\frac{cn}{2^j}$ to the recurrence relation. Thus, we have (for $n\ge 2$): \[T(n)\le \sum_{j=0}^{\log_2{n}} \frac{cn}{2^j} =cn\cdot \sum_{j=0}^{\log_2{n}} \frac{1}{2^j}.\]

Working out this geometric sum, we will find that it converges to $2$. Thus, we can say, for recurrence relation 2 above we have \[T(n) \le 2cn \le O(n).\]

HW 6, Question 2

Figuring out the boundaries

In the algorithm in the text, for each point in $S_y$ (the list of points in the $2 \delta$-wide strip around L, sorted by $y$-coordinate), we compute the distance to the next $\alpha = 15$ points in the list. One thing we must formalize is the behavior at the boundaries of each of these boxes. In order to prevent points that lie on one of the vertical boundaries ($x = x^*$, $x = x^* \pm \frac{\delta}{2}$, and $x = x^* \pm \delta$) from being placed in both of the adjacent boxes, we will consider that points on these lines are in the box to the left. (In particular, at point with $x=x^*-\delta$ will not be in $S$.) We will also consider that any points on the horizontal boundaries between the boxes belong to the box above the boundary. Even with these new boundary conditions, it is easy to see that the argument we saw in class still implies that every $\frac{\delta}{2}\times \frac{\delta}{2}$ square/box can have only one point in it.

We will assume the above for the rest of the recitation notes and you can assume them for your solutions as well (as long as you explicitly refer to these recitation notes).

Part (a)

Problem

Show that the Kickass property lemma holds for some $\alpha \le 11$ so that the lemma still holds if one replaced $15$ by $\alpha$ in the lemma statement.

Proof Idea

We will show that this can be done by considering only the next $\alpha = 11$ points in the list. Let's call the current point we are considering $p$. Since we are finding the distance only to points with larger $y$-values, we can assume that the point $p$ is in one of the boxes in the first (bottom) row. We can then eliminate the row of boxes that are the third row from the bottom one from contention because all of the points in that top row of boxes must $\ge \delta$ apart from $p$ (due to the following lemma, which you will need to prove).

Lemma 1

Consider any point $p$ in a row of boxes. Let $q$ be any point in the third row of boxes above the row that contains $p$. Then $d(p,q)\ge \delta$.

Even though it is not needed for your submission, we also provide the proof details:

Proof Details

The point $p$ is in some box on the bottom row. Suppose that $p$ is as close to the upper boundary of its box as it can be without actually being on it, say some arbitrarily small distance $\epsilon$ below. Now, suppose that there exists a point in the third row of boxes (above $p$'s row) which has the same $x$-coordinate as $p$, call it $s$. Further, suppose that $s$ is on the lower boundary of its box. Based on these assumptions, $d(p,s) = \delta + \epsilon > \delta$. However, eliminating any of these assumptions would increase the distance between $p$ and $s$: if $p$ was a greater distance from its upper boundary, $d(p,s)$ would increase; if $s$ had a different $x$-coordinate, $d(p,s)$ would increase; and if $s$ was not on the lower boundary of its box, then $d(p,s)$ would once again increase. Therefore, for any point in the third row of boxes (above $p$'s row), its distance to the point being considered, $p$, will never be less than $\delta$. Therefore, we we're left with three rows of four boxes (including $p$'s row) each where points can reside which could be within a distance $\delta$ of $p$. Since $p$ is by itself in one of those 12 boxes, we must only compare $p$ to the next 11 points in the list.

Part (b)

Problem

Prove that the Kickass property lemma holds for some $\alpha \le 9$ so that the lemma still holds if one replaced $15$ by $\alpha$ in the lemma statement.

Note

One can actually prove the statement with $\alpha=7$ but any argument for $\alpha\le 9$ is enough.

One potential way to argue $\alpha=9$ is to consider the argument above for $\alpha=11$ and to then tighten the argument a bit to reduce $\alpha$ to $9$.

Prim's Algorithm

Similar in functionality to Dijkstra's algorithm.

Example

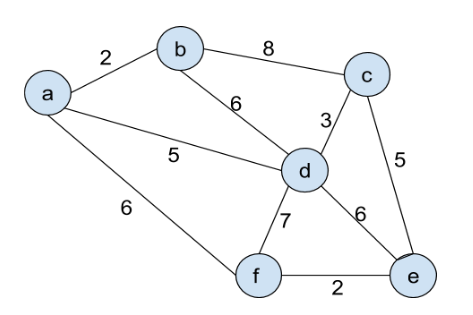

Run Prim's algorithm on the input:

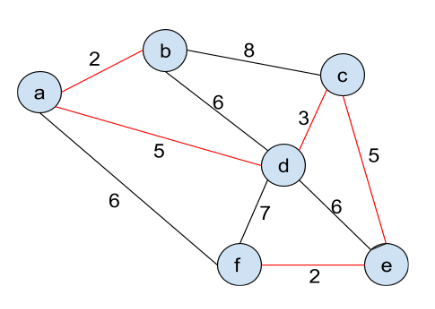

The following is the output:

Further Reading

- Section 5.2 in the textbook.

- Support page on integer multiplication.